Clinton’s Role in the Gold Rush

The clang of pickaxes echoed through the Fraser Canyon, the scent of pine and dust thick in the air. Boots, heavy with mud, trudged along a well-worn path, kicking up clouds of earth as fortune-seekers pressed northward. Their destination? The fabled gold fields of the Cariboo. Their path? A rugged, unforgiving trail where hunger, exhaustion, and bandits lurked around every bend.

But along that perilous route, one town stood as a beacon of rest and resupply—Clinton, British Columbia.

Before the Gold Rush, Clinton was nothing more than a remote stretch of land nestled within the traditional territories of the Secwépemc and St’át’imc First Nations. But as thousands of miners, traders, and adventurers surged through the Fraser Canyon, the need for rest stops and supply hubs became vital. Clinton quickly transformed into a bustling waypoint where weary travelers replenished supplies, blacksmiths repaired wagon wheels, and stagecoach passengers found a warm meal and a bed before continuing their journey into the gold-laden hills beyond.

But Clinton’s story is more than just a waypoint on a map—it is a tale of resilience, ambition, and transformation. The town was shaped by the merchants who saw opportunity beyond gold, the Indigenous guides who helped travelers survive the unforgiving terrain, and the pioneers who built the businesses and homes that still stand today.

Though the gold rush faded, Clinton endured, evolving from a transient supply post into a community with a rich and lasting heritage. In this article, we’ll uncover the forgotten stories of Clinton’s Gold Rush era—from the hopeful miners who passed through its streets to the local entrepreneurs who turned a frontier boomtown into a thriving village.

Step back in time with us as we journey along the Cariboo Trail, where history whispers through the streets of Clinton.

The Fever for Gold: The Birth of the Cariboo Gold Rush

Gold has always had a way of igniting dreams. It is the great equalizer—the promise that no matter one’s past, a golden future might still lie ahead. And in 1858, that promise lured thousands to the untamed wilderness of British Columbia.

It began, as all great rushes do, with a whisper. A few glimmers of gold dust found along the banks of the Fraser River, a quiet murmur among prospectors, a rumor that grew louder until it roared across the continent. The news spread like wildfire, leaping from the mining camps of California to the cobbled streets of London, from the saloons of San Francisco to the farmlands of the eastern United States. Soon, steamers packed with wide-eyed hopefuls arrived in Victoria, their passengers pouring into the new colony with little more than a shovel, a pickaxe, and a gambler’s faith in fate.

But this was no easy strike. Unlike the compact and accessible goldfields of California, British Columbia’s riches were buried deep in the rugged Cariboo Mountains, locked beneath layers of rock and gravel, waiting only for those determined enough to reach them. The journey alone was a test of endurance. Miners had to navigate raging rivers, climb steep canyon walls, and trudge through miles of dense wilderness where supplies were scarce, the roads treacherous, and the promise of wealth just as often led to ruin.

Yet still, they came.

With thousands of men—and the merchants who followed them—pushing deeper into the interior, it became clear that an overland route was desperately needed. A path was carved out of the wilderness, winding through the thick pine forests and over rocky mountain passes, stretching from the Fraser Canyon to the distant diggings of Barkerville. This was the Cariboo Trail, and along its well-worn path, settlements began to take root.

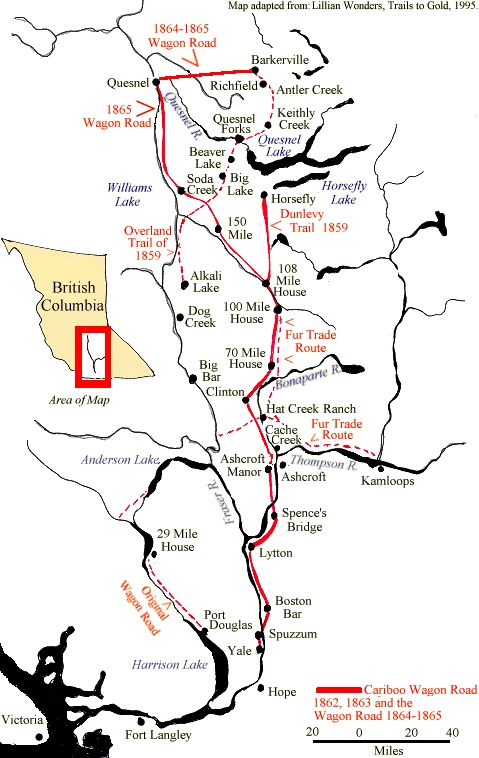

This historical map illustrates the Cariboo Wagon Road, a crucial lifeline for miners and merchants during the Cariboo Gold Rush (1862-1865). Stretching from Yale to Barkerville, the road passed through key towns, including Clinton, which served as a major supply hub for fortune-seekers heading north.

And at Mile 47, Clinton was born.

At first, it was little more than a stopping point, a place where weary travelers could rest their horses and take refuge from the elements. But as the Cariboo Trail grew busier, Clinton transformed. A blacksmith set up shop, hammering out fresh horseshoes for pack animals on their last legs. A general store was built, stocked with flour, beans, and the sturdy tools of the trade. Before long, an inn welcomed exhausted miners looking for a hot meal, a stiff drink, and a chance to share tales of fortune—or misfortune—before setting out again at first light.

Some stayed only long enough to refill their supplies. Others never left.

Clinton, unlike the wilder boomtowns that erupted overnight and vanished just as quickly, had something that set it apart: permanence. It was a town built not on gold, but on the movement of people—the restless tide of prospectors, traders, and adventurers passing through its streets. As long as there were men willing to chase a fortune in the Cariboo, Clinton’s future seemed secure.

Yet the Gold Rush was more than just miners and merchants. The town bore witness to the stories of all who walked its streets. Indigenous traders, who had known these lands long before a single miner set foot on the trail, offered their knowledge, guiding those who would listen through the unforgiving terrain. Chinese laborers, many escaping hardship in their homeland, built roads, bridges, and businesses, their sweat paving the very route that made Clinton possible. Women, often overlooked in frontier history, ran the roadhouses and taverns, some carving out small empires of their own in a world dominated by men.

For Clinton, the rush for gold was never just about the metal hidden in the hills. It was about the people drawn to its promise, the town that rose from their ambition, and the stories—some triumphant, others tragic—that linger in the dust of the Cariboo Trail.

Clinton: A Gold Rush Crossroads

By the time a weary traveler reached Clinton, the weight of the journey was etched into every fiber of his being. His boots, once sturdy, were worn thin by the relentless grind of the trail. His pack, once filled with optimism, now carried only the bare essentials—flour, salt pork, and enough hardtack to stave off hunger. His horse, if he still had one, was little more than skin and bone, having trudged through the thick forests and steep inclines of the Cariboo Trail.

Yet here, at Mile 47, the journey paused.

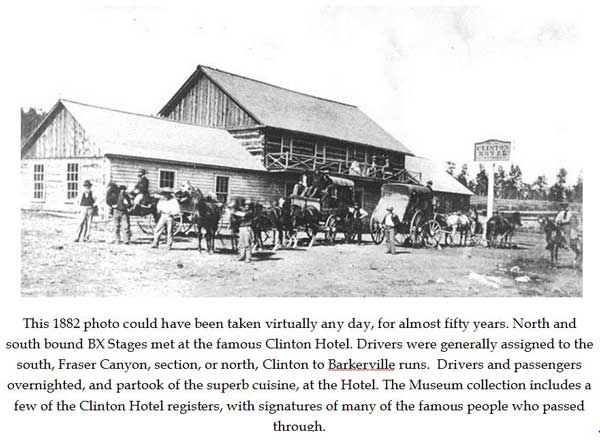

BX Stagecoaches at the Clinton Hotel (1882) – A historic hub for Cariboo Gold Rush travelers and pioneers.

Clinton was more than just a stop along the way—it was a lifeline for those heading north. No matter how determined a miner was to reach the goldfields, he could go no further without fresh supplies, a repaired wagon, or a night’s rest under a proper roof. It was a town that thrived on movement, built not on gold itself but on the restless tide of those who chased it.

During the peak of the Cariboo Gold Rush, Clinton pulsed with the energy of a town on the edge of history. Horses clattered down the dirt streets, their breath rising in plumes against the early morning air. Blacksmiths hammered away in their forges, the scent of burning iron mingling with the rich aroma of bread from the bakery. Shopkeepers stood in the doorways of their general stores, calling out to travelers with the promise of fresh provisions, warm meals, and a bed that didn’t shift with the wind.

Everywhere, there were stories.

A merchant from Victoria unloading crates of coffee and whiskey, trading at triple the price for those willing to pay. A pack train of mules, their backs laden with tools, making the slow trek up the mountain pass. A prospector, fresh from Barkerville, his pockets jingling with newfound wealth, buying rounds for the entire tavern. And in the corner, a man who had seen too many winters on the trail, his silence telling a tale of gold that had slipped through his fingers.

But it wasn’t only the fortune-seekers who built Clinton. The town owed much of its existence to those who saw opportunity beyond the mines. Blacksmiths, tailors, and carpenters set up shop, knowing that miners with aching backs and empty stomachs would always need horseshoes, warm coats, and sturdy tools. Taverns and inns filled with the laughter (and the occasional brawl) of men who had spent months in the wilderness, eager for a taste of civilization.

Among these early entrepreneurs were the women of Clinton, many of whom ran the roadhouses and hotels that kept the town alive. In an era when few women were seen as independent business owners, Clinton’s Gold Rush economy allowed some to carve out their own success. These were not women of high society but tough, sharp-witted pioneers who knew how to turn a profit from the chaos of the trail.

Indigenous traders, too, played a vital role in Clinton’s rise. The Secwépemc and St’át’imc peoples had known these lands long before the first wagon wheel cut into the Cariboo Trail. They provided food, furs, and guidance, showing travelers the safest river crossings and the hidden trails that wound through the mountains. Yet, as settlers flooded into the region, their lands and way of life were altered forever.

And then there were the Chinese immigrants, many of whom had first come to British Columbia during the Fraser River Gold Rush. While some sought gold, others built their own businesses—laundries, gardens, and supply shops that served the growing population of Clinton. Despite the racism and exclusionary policies they often faced, their contributions to the town’s development were undeniable.

Clinton had become a town of momentum. As long as men moved north in search of gold, it thrived. The roads were never empty, the inns never quiet, the fires in the forges never cold.

Yet, like all boomtowns built on the backs of miners, the question loomed: What would happen when the gold ran out?

The Challenges and Dangers of Gold Rush Travel

The Cariboo Trail was not meant for the faint of heart.

For every man who arrived in Clinton with pockets full of gold dust, a dozen more never made it past the brutal wilderness that lay between the Fraser River and the distant goldfields. The journey north was not simply a test of endurance—it was a battle against the very land itself.

From the moment a prospector set foot on the trail, he was at the mercy of forces beyond his control. The path wound through dense forests, where towering pines swallowed the daylight and the silence pressed in like a weight. Raging rivers cut across the route, their icy waters swallowing carts, horses, and men alike. In the winter, blizzards buried the trail beneath feet of snow, turning the road into an impassable tomb of white. In the summer, the sun baked the earth into a dust-choked wasteland, where water was scarce and every step forward kicked up a storm of grit.

The road to the goldfields was paved with suffering. Countless prospectors set out on foot, carrying everything they owned on their backs—tools, provisions, and the fragile hope that the journey would be worth it. Others had the luxury of a wagon, though luxury was a loose term. The wheels creaked under the weight of supplies, and more than a few were abandoned when the terrain became too steep to carry them further. The lucky ones had horses or mules, but even they were not spared the hardship. Many an animal collapsed along the trail, their bodies left behind as grim reminders of the journey’s cost.

Then there were the bandits. The gold rush was not just a race for fortune—it was a hunter’s game, and not all men played by the same rules. Along the more isolated stretches of the Cariboo Trail, thieves lurked in the shadows, waiting for a lone prospector who had struck it rich. Armed with pistols and knives, they preyed upon those who had let their guard down, knowing that justice was a luxury few could afford on the frontier. More than one traveler vanished along the trail, his fate known only to the whispering pines and the shallow graves that dotted the roadside.

In response, Clinton became an unofficial outpost of law and order. As one of the last major stops before the goldfields, the town saw its share of lawmen—and lawbreakers. Mounted police patrolled the streets, and more than one saloon fight ended with a swift, hard lesson in frontier justice. The townspeople knew that while Clinton thrived on the movement of men and money, it could not survive if lawlessness took hold.

Yet despite the dangers, despite the risk of starvation, injury, or theft, men kept coming. Perhaps it was the lure of gold that blinded them to the perils ahead. Perhaps it was the belief that fortune favored the bold. Or perhaps it was something deeper—a refusal to accept the lives they had left behind, a desperate hope that somewhere in the cold rivers of the north, fate had set aside a nugget just for them.

But the Cariboo Trail had little mercy. For every man who struck it rich, a hundred more returned to Clinton with nothing but calloused hands and an emptiness they could not shake. Some turned back toward the cities of the south, their dreams shattered. Others lingered in Clinton, reluctant to admit defeat, trading their pickaxes for the tools of another trade.

And some, unable to bear the thought of returning home empty-handed, simply vanished into the wilderness, becoming part of the land itself.

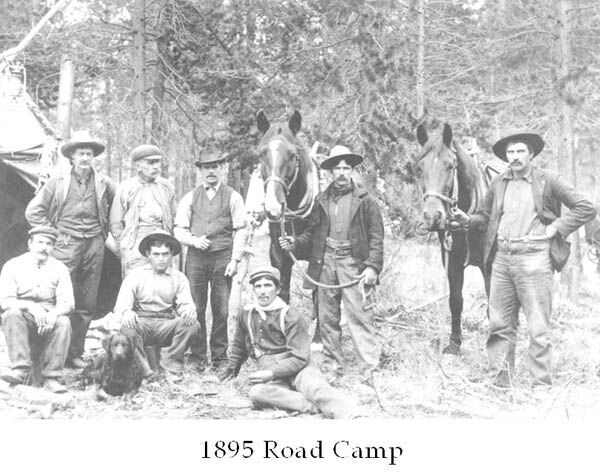

1895 Road Camp – A glimpse into the lives of Cariboo Trail pioneers who helped shape Gold Rush towns in BC.

The Cariboo Wagon Road: Clinton’s Lifeline

The Cariboo Trail had always been a road of necessity—born not from careful planning, but from the sheer desperation of thousands pushing north toward the promise of gold. It was rough, treacherous, and barely passable in places, yet it was the only way forward. But as the flow of miners and merchants swelled, the colony’s leaders realized that something more was needed.

A proper road. A lifeline to the goldfields. In 1862, Governor James Douglas ordered the construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road, an ambitious project designed to tame the wild terrain and open British Columbia’s interior to trade and settlement. It was a feat of engineering unlike anything the colony had seen before—bridges had to be built over raging rivers, sheer cliffs carved into pathways, and miles of wilderness tamed into something fit for heavy wagons and stagecoaches. The cost was staggering, the labor backbreaking, but the reward was undeniable: a road that would link the outside world to the gold-rich heart of the Cariboo.

And Clinton, perched at Mile 47, was one of the greatest beneficiaries. Where once it had been a modest stopping post for weary travelers, Clinton was now a vital hub on the most important road in British Columbia. The dirt paths of the past were widened and reinforced, allowing wagons to roll through town with ease. Stagecoaches, heavy with passengers, thundered down the main street, kicking up clouds of dust as they pulled up to the inns and roadhouses that lined the way. The flow of goods increased—barrels of flour, crates of tools, sacks of coffee and sugar—all making their way through Clinton before continuing north to supply the miners.

And with the road came the people who built it. The construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road brought in an entirely new workforce—hundreds of laborers, including large numbers of Chinese workers, who toiled in harsh conditions, blasting through rock, laying timber supports, and digging out sections by hand. The road was their legacy, though few would ever be recognized for their contribution. Their labor made Clinton’s prosperity possible, even as they were often forced to live on the fringes of the settlements they helped build.

With a steady stream of travelers passing through, Clinton flourished in ways few had imagined. New businesses opened, catering to both those on the move and those who chose to stay. Blacksmiths worked tirelessly to keep wagons in repair, tailors stitched durable clothes for miners, and roadhouses did brisk business, filling their tables every evening with the laughter of men eager for a warm meal and a drink before the next leg of their journey.

For years, the Cariboo Wagon Road was the pulse of Clinton—its very reason for existence. Every traveler who passed through, every cart that rattled down its roads, every miner who stopped for supplies, added to its prosperity. But as with all roads, it was not meant to last forever.

As the goldfields dwindled and the rush began to fade, so too did the need for the Cariboo Wagon Road. With fewer travelers, Clinton’s future seemed uncertain. Could a town built on movement survive once the journey north no longer held the same promise?

The gold was running out. And Clinton would have to decide whether it was a town that lived or died with it.

The Decline of the Gold Rush and Clinton’s Resilience

Gold was never meant to last forever.

By the late 1860s, the rush that had once consumed British Columbia was beginning to slow. The richest deposits in the Cariboo had been stripped away, and while miners still worked the rivers and mountains, the great caravans of hopefuls that had once surged through Clinton became fewer with each passing season. The fever that had built the town was fading, and with it, the movement that had sustained its economy.

The signs were impossible to ignore. Storefronts that once bustled with business saw fewer and fewer customers. Roadhouses that had overflowed with rowdy miners now had empty tables. The Cariboo Wagon Road, once a highway of fortune-seekers, grew quieter. The gold was disappearing, and Clinton was at a crossroads.

Many of the towns that had sprung up during the Gold Rush faded into obscurity, abandoned as quickly as they had been built. But Clinton was different.

It had never relied solely on gold to sustain itself. While many saw Clinton as a mere stop along the Cariboo Trail, the town had grown into something more—a community built not just on the pursuit of wealth, but on the resilience of those who had settled there. The same blacksmiths, tailors, and merchants who had once catered to miners now turned their skills toward serving the growing population that remained. Ranchers and farmers expanded their trade, providing food and livestock for the townspeople who had chosen to make Clinton their permanent home.

New industries emerged to take the place of gold. Ranching became a pillar of the local economy, as the open grasslands surrounding Clinton proved perfect for cattle and horses. Forestry grew in importance, with timber from the surrounding hills feeding the construction of new homes, businesses, and railroads across the province. The town adapted, shifting from a Gold Rush boomtown into a self-sustaining community with deep roots.

Clinton’s people, too, proved themselves to be as enduring as the land itself. While many mining towns vanished into the pages of history, Clinton remained—a testament to the stubborn determination of those who refused to let their town fade into obscurity. The buildings, the businesses, and the families that had grown with the town carried it forward into a new era, proving that Clinton’s story was far from over.

Even as the Gold Rush came to an end, Clinton stood. And it still stands today.

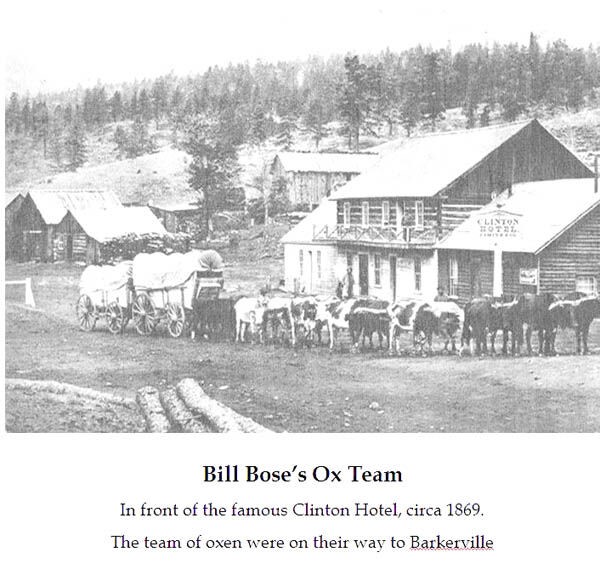

Bill Bose’s Ox Team, Clinton BC (1869) – A vital part of historic travel in British Columbia during the Cariboo Gold Rush.

The Legacy of the Gold Rush in Clinton Today

The dust of the Gold Rush has long since settled, but if you listen closely, you can still hear the echoes of history in Clinton. The clatter of wagon wheels on the Cariboo Wagon Road may be gone, but its path still winds through the heart of town. The miners who once filled the inns and taverns have faded into memory, but their stories remain, woven into the very fabric of Clinton’s identity.

Though the goldfields no longer call fortune-seekers north, Clinton has never forgotten its roots. The town still bears the marks of its past—the old buildings, weathered by time, stand as silent witnesses to the era that built them. The Clinton Museum, housed in a historic structure that once served as a schoolhouse, offers a glimpse into the lives of those who passed through or stayed, their relics telling the story of hardship, ambition, and resilience.

But Clinton’s connection to its Gold Rush past is more than just artifacts and preserved buildings—it lives on in the spirit of the community. Every year, heritage celebrations and events pay tribute to the pioneers who shaped the town. Local businesses, some tracing their lineage back to the days of the Cariboo Wagon Road, continue to serve both residents and visitors with the same hospitality that once greeted weary travelers more than a century ago.

For those who visit today, Clinton offers a chance to step back in time. Walk its streets, and you may find yourself imagining the scene as it once was—dust swirling in the air as a stagecoach arrives, horses tied to hitching posts, a blacksmith hammering out a fresh set of shoes in his forge. The past lingers here, waiting to be rediscovered by those who take the time to listen.

But Clinton is not just a town of memories—it is a town that endures. The same resilience that saw it through the Gold Rush remains in the people who call it home today. Though the industries may have changed, the determination to build, to grow, and to preserve what came before remains as strong as ever.

So whether you are a traveler passing through, a historian searching for stories, or a resident walking streets lined with history, know this—Clinton’s legacy is not just in the past. It is alive, carried forward by every person who calls this place home.

The Gold Rush may have come and gone, but Clinton still stands. A town once built on movement has found permanence. The same land that bore witness to thousands seeking their fortunes now welcomes those seeking something else—a connection to the past, a sense of history, and the enduring spirit of a town that refused to disappear.

Clinton was never just a stop on the Cariboo Trail. It was, and still is, a place where history lives.

Community

Community Council

Council Reports &

Reports &